Claims about the remarkable progress of computer technology abound. Today’s devices aren’t merely faster and endowed with storage capacities once unimaginable – they also run sophisticated software that would have seemed like science fiction to earlier generations. Groundbreaking leaps in artificial intelligence – especially transformer algorithms powering Large Language Models (LLMs) – have enabled possibilities that were once beyond our wildest dreams. Yet, at their core, the essence of what makes a computer has remained unchanged.

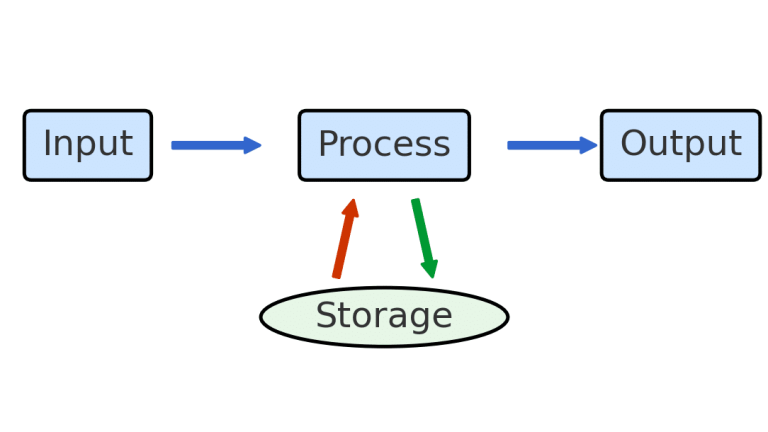

Since the earliest days, computing has been based on a model with four elements: Input, Processing, Storage and Output. The computer takes some input, processes it in some way, utilising temporary or permanent storage to do so, and produces some output.

Take the humble pocket calculator. We enter 6 multiplied by 4. The calculator recalls the method for performing multiplication from storage. It then processes the numbers 6 and 4 according to this process. Finally, it outputs the number 24. LLMs, such as ChatGPT and Gemini, work in a similar manner. We enter a prompt – for example, “write me a sonnet on the Forth Bridge” – and, after performing its internal processing, the LLM delivers some text as output. It is the same when the output is an image, video, music, the next move in a game of chess, or the prediction of how a protein molecule might fold in three dimensions.

This framework underpins the legendary Turing Test, the classic measure of machine intelligence. A user submits questions (input), and the AI’s responses (output) are scrutinised: if a human judge can’t distinguish machine from person, the AI is deemed “intelligent”.

Beyond AI and the Turing Test, we see this Input-Process-Output model for assessing intelligence in the wider world. The examiner sets a question (the input) which the student ponders (the processing), drawing on all they remember (the storage) before writing an essay (the output). We see similar patterns in the TV quiz show and the job interview. The Input-Process-Output model is so prevalent that we have come to believe it represents intelligence. If a person cannot produce a suitable output given some input, then many would judge that person to be unintelligent.

But this is wrong. We have been deceived by applying machine models to human thought. Much of our mental life, even our intelligence, has nothing to do with Input-Process-Output. Here are some examples.

I am packing to go on holiday. Even though the weather is beautiful, at the last minute I remember to take a waterproof coat, just in case. Here there is no specific input. This idea for suitable clothing (the output) has sprung from my internal, ongoing thoughts, experiences and imagination. In an AI system, there are no ongoing internal “thoughts”. While it is waiting for my next prompt, it is not “thinking” about anything. So, there is no possibility of spontaneous, unprompted action.

I am searching through a cupboard when I find some old photographs of my childhood. As I look through them, not only do I recall the different events, but I also remember how I was feeling – and I experience feelings now. A picture of my grandfather reminds me of the happy times we had together, and the sadness of his passing. Here, although there is input in the form of the photographs, there is no specific output. Again, this is very different from the AI model of Input-Process-Output.

I am walking through the park with a friend. The friend has just been made redundant and will no longer be able to afford the mortgage payments on their family home. They are desperately worried. I know I don’t need to say anything. Simply being with them in their anxiety is enough. To adopt an Input-Process-Output approach would be to trivialise their distress.

I also question whether some of the greatest creative acts of genius could really have been nothing but the result of Input-Process-Output. The music of Mozart, the painting of Van Gogh and the mathematics of Gödel all spring to mind.

As a final example, consider Christian faith. Each morning, as I spend time in prayer, my eyes are closed, and I am focusing inward. There is no input. Moreover, nothing happens as a result of my prayer – I neither speak, write, nor act. There is no output. But during this time, I feel myself drawn closer to God. I find that my life is being transformed as my sins are forgiven, my trust in God increases and my love for others grows. Prayerful contemplation is the antithesis of the Input-Process-Output model.

This is hardly surprising for we are made in the image of God. God, being complete and independent, does not require input to think, speak or act. Nobody has to feed God with suitable prompts. Likewise, God could have chosen just to be. Creation – God’s output – was a freely chosen divine act and not an inevitably necessary outcome of some heavenly algorithm.

The Input-Process-Output model has been instrumental in the world of computing. But we must not let the functioning of a computer define intelligence. Even more importantly, we must not allow this approach to limit what it means to be human. As creatures made in the image of God, our lives are far richer and more profound than the operations of a machine.